Every vital machine stopped working

By Kinya Kaunjuga

The power blackout was going into its fifth day. It had been a nightmare trying to treat patients.

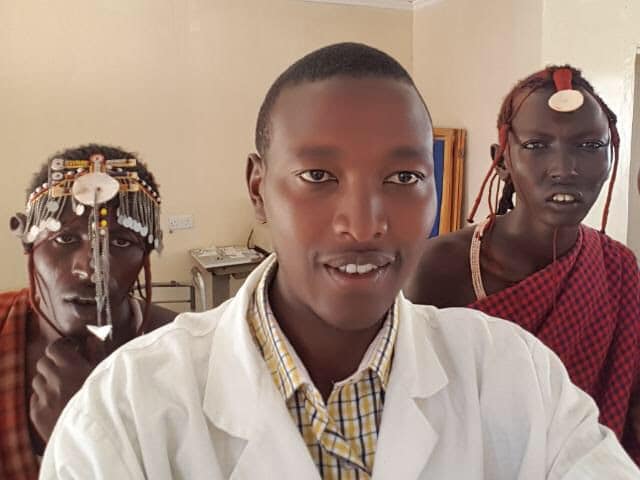

This was how the clinical officer in-charge, Leonard Loontaye described the effect of El Niño rains on his clinic, Naikarra Medical Center. When he called me, he was staring at the fallen transformer he pictured below.

He narrated what he and the communities around his clinic experienced in the last weeks of December 2023.

Our solar backup power couldn’t keep up with the length of the blackout and every battery had been exhausted. We couldn’t work. I needed tests done to confirm diagnoses and we couldn’t do any lab tests. The laboratory refrigerator went off so samples, specimens, vaccines and medications were compromised.

The maternity sterilizer and oxygen concentrator had stopped working. Sunlight takes a long time to fully re-charge a completely depleted battery.

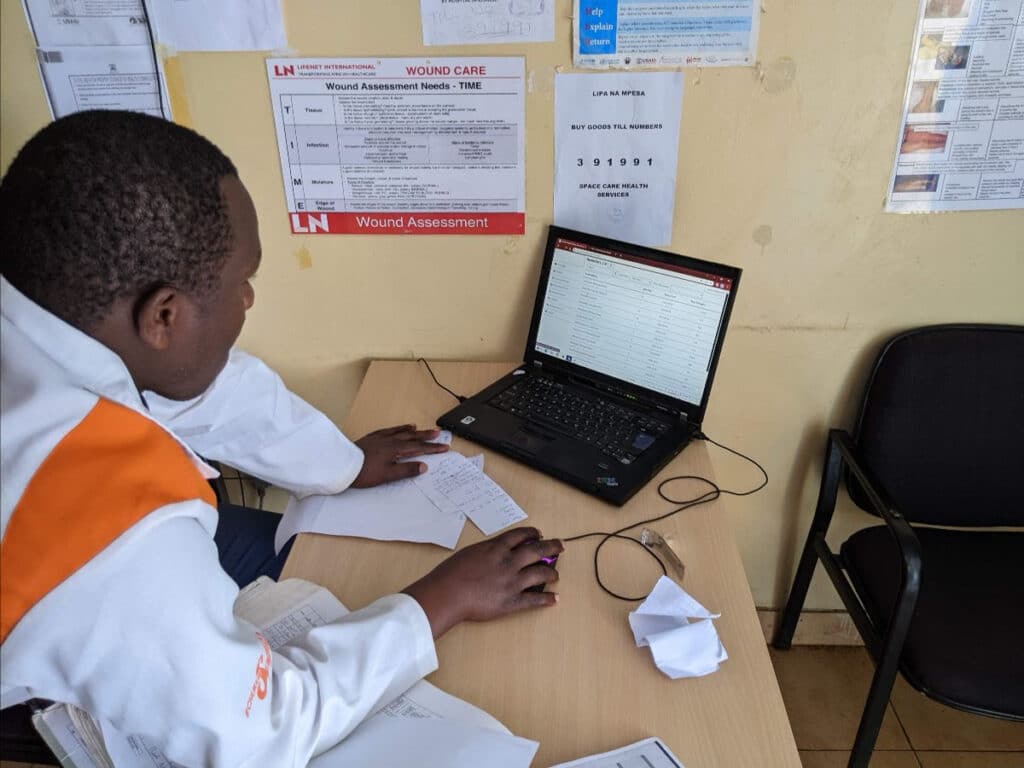

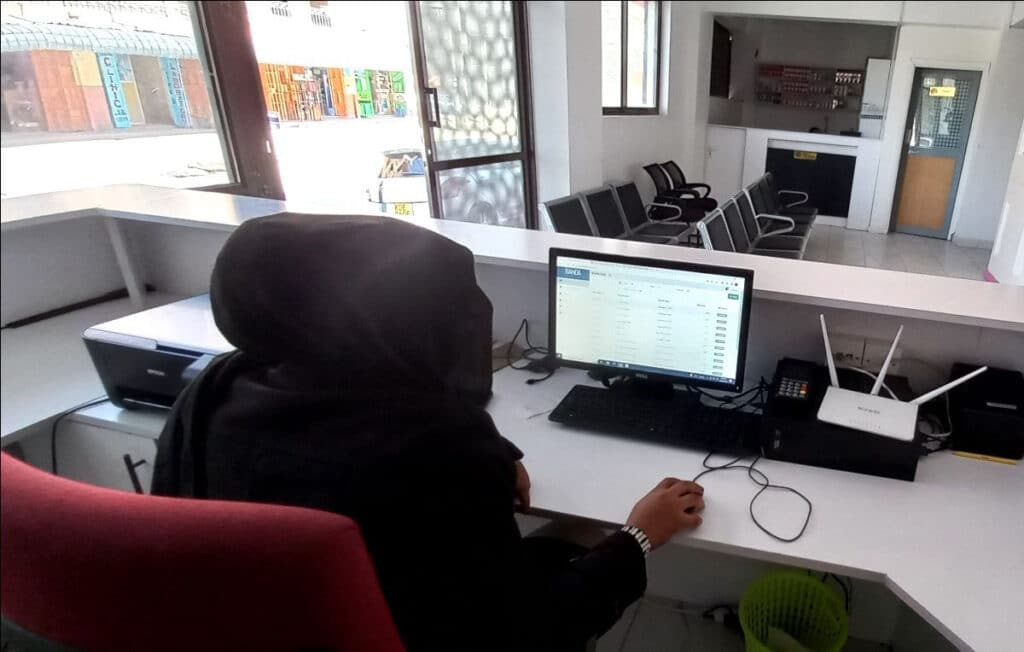

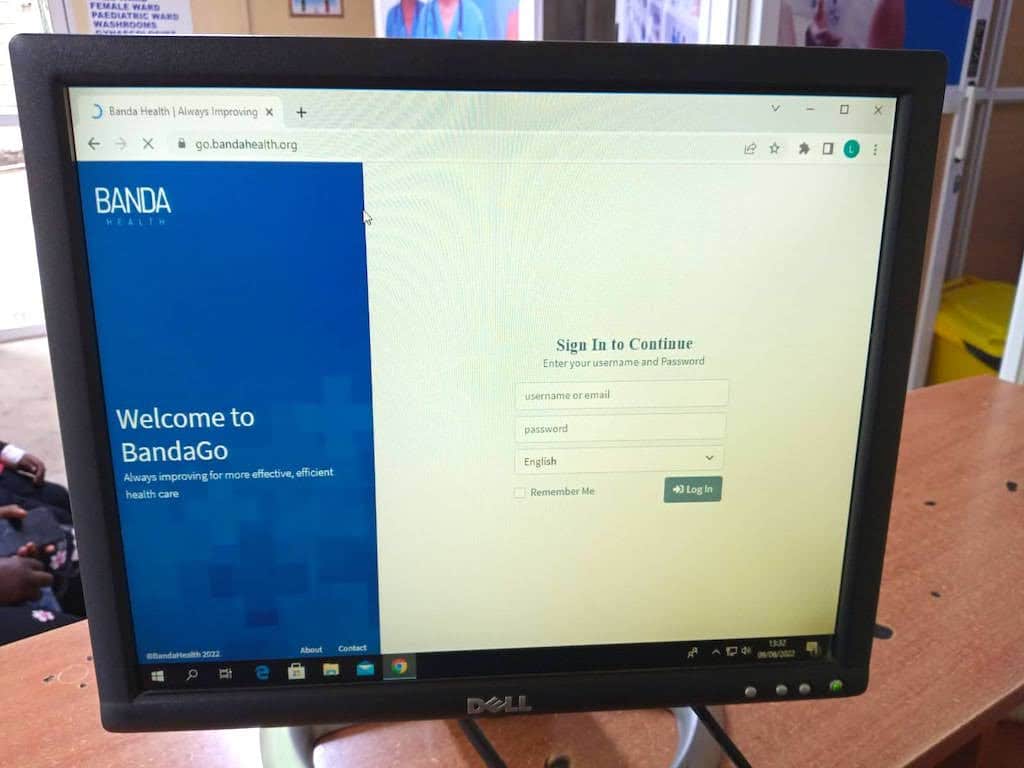

Fortunately, we rely on BandaGo for our clinic management. As it operates online, we didn’t have any concerns about patient visit records, medicine and supplies inventory data, or accounting information being jeopardized by power fluctuations caused by an unstable grid.

We had to keep one particular patient outside the clinic. It was the only way to isolate her from the other patients before we confirmed whether she had tuberculosis (TB). It could easily spread throughout the entire clinic.

She had been sick for some time but needed to complete her exams which took 3 weeks in her high-school. If found positive for TB it meant everyone around her had been exposed to the bacteria.

We only hoped the community health volunteer had intercepted in time to prevent the student from exposing too many people to the deadly disease.

Since the TB hood was also not working, we had to modify a way to process the patient’s specimen slides manually. It was a great risk to the lab technician but the patient had been waiting for almost 4 hours for the batteries to charge using the solar panels and she was completely fatigued.

The test revealed that the patient had pulmonary TB, and the community health volunteer was quickly notified so that she could visit the patient’s family and school and implement critical public health measures carried out when tuberculosis has been confirmed in a patient.

The test results also meant that Leonard Loontaye, the clinical officer in-charge at the Naikarra Medical Center, along with the lab technician, had been directly exposed to the bacteria.

They were keenly aware of the importance of swift and comprehensive actions in the face of a possible TB diagnosis and had put themselves at risk by deciding not to keep waiting for electricity to return to power up their protective lab equipment.

A disease dating back to 8000 BCE

“TB is one of the world’s leading infectious disease killers. Until the emergence of COVID-19, the bacterium that causes TB was described as, “the most destructive pathogen on the planet,” killing more than 4,300 people each day. Despite being preventable, treatable, and curable, this ancient disease continues to kill more people each year than HIV and malaria combined. While a wide range of evidence-based and scientific interventions have been developed to combat TB, due to continued underinvestment and low global prioritization (compared to other diseases), TB persists, resulting in close to 11 million TB cases and 1.6 million deaths annually.” Source: USAID’s Global Tuberculosis (TB) Strategy 2023–2030.

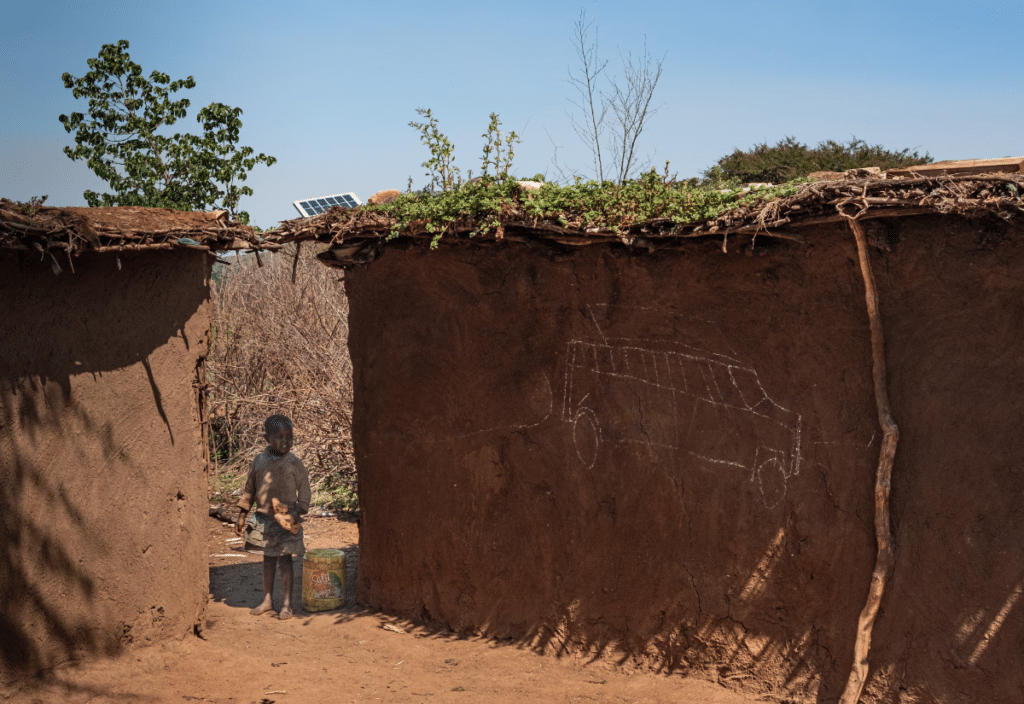

Energy poverty

“Energy poverty can be explained by the lack of infrastructure, well-functioning energy services markets, and sufficient income to afford modern energy sources. Energy poverty in developing countries affects the entire territorial units. The rural and remote areas remain particularly disadvantaged, with no or little access to modern energy sources.” Source: Energy poverty in developing countries: A review of the concept and its measurements, Energy Research & Social Science, Volume 89, 2022.

$5000 helps us improve BandaGo and get it into another clinic

Medical clinics that use our clinic management system BandaGo have one less critical thing to worry about when treating patients in extreme hardship areas.

Thanks to your giving, Banda Health continues to focus on building technology solutions that improve the healthcare provided in medical clinics run by some of the most brave and selfless people on the globe.

Photo credits: Power for All; Solar Aid; Reachout Consortium ‘Implications of community health policy change in Kenya in light of world health worker week’ by Rosalind McCollum; Banda Health.

Kinya Kaunjuga

Kinya brings passion, an infectious laugh and 15 years of experience in the corporate and non-profit world to Banda Health. A Texas A&M alumni with a degree in Journalism and Economics, she says, "I love doing things that matter!"