Share Everything or Risk Losing It

By Kinya Kaunjuga

“If they rob you, tell them you know me and they might return your phone.” This instruction was part of the preparation for a visit to one of the clinics that uses BandaGo. It wasn’t obvious that the entrance to the road leading to the clinic was manned in shifts by gangs. In fact, everyone was busy.

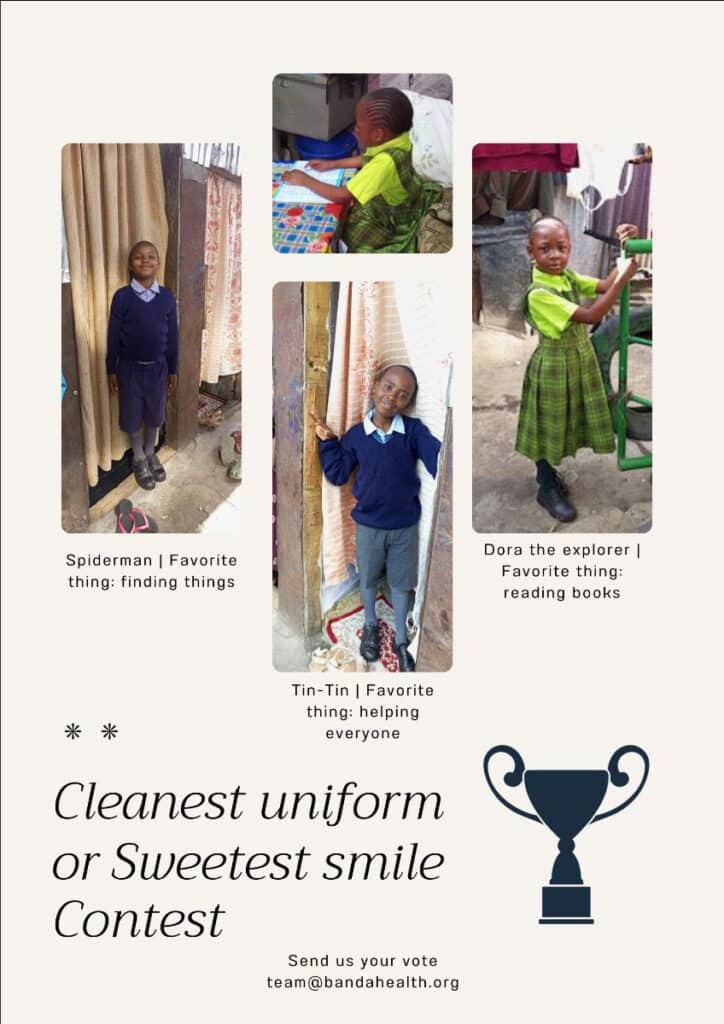

Children walking back from school dodged garbage to avoid smudging their uniforms, veggie bandas (kiosks) selling chopped kale were now crowded by customers who preferred to skip that step in their cooking prep, and the queue outside the communal bathing stall was growing. I learnt that you can wash your entire body with one 350ml cup of water, the size of a can of coke.

What we call a slum, those born there call a ghetto. This means it’s a place where every day is tough to live through and every night is rough. That it’s only different from other places because their homes have no windows and are made out of mud, cardboard and metal sheets pieced together with sticks and stuff. That all their water is fetched from an outside faucet shared by slightly more than 200,000 people, and that indoor plumbing doesn’t exist but one can pay to use a communal bathing stall and toilet that’s emptied now and then.

All this sharing of the most basic things seems to indicate that patience is a critical survival characteristic for a poor person, followed closely by settling on never having space, privacy, or ownership. Adults and children begin to line up for everything from as early as 4 am. As a result, some of the residents make some money by charging to hold a spot in queues to use a toilet, a bathing stall and a water faucet.

As darkness fell in Nairobi, the October night felt utterly still. There was no wind and the air was so hot, it made being indoors feel unbearable.

The cab guy was nervous. I assured him that we would be safe because I had some people waiting for us at a clinic that uses our software. This did not seem to reassure him at all, especially when he recognized the road we would be turning onto since it had featured on the news for months during recent political demonstrations in the country.

For countless days during the demonstrations, Uzima White and his staff had faced complete mayhem. Because his little clinic is in the middle of the slum, there was a non-stop flow of injured people and he had turned parts of it into a medical emergency refuge while continuing to care for regular patients in his small ward.

“At one point I realized we would have to lock the main door to prevent the crowd who were carrying the injured from pushing into the clinic. I was shouting at the top of my voice pleading with them to stop crushing each other but they couldn’t stop in the chaos. So my staff and I would shut the doors, treat those inside and re-open the doors to take the next ones.

“Ambulances were having a hard time reaching the clinic because of the exchange of stones and gunfire, and barricades like burning tires on the road. A 17-year-old’s last words to me when an ambulance finally arrived to pick him up were, “My mother told me not to join the demonstrations.” I had treated him for a gunshot wound that had severed his groin. He died before the ambulance reached the hospital.

“That memory stays with me because I have a freshman and a sophomore in college now. In fact, it affected me more than the gunshots being fired outside the clinic.

“When we would open the door to let the injured in and out, the soldiers would yell, “Doctor, shut your door!” I remember a patient I was examining who kept screaming each time a gunshot went off. She asked me, “Doctor, aren’t you afraid of the gunshots?” And I responded, “What shots?” She and the others around her looked at me incredulously. I didn’t realize that I had become so used to hearing the gunshots that I didn’t flinch when they went off anymore. It made me wonder if I would have been a better soldier than a medic.”

“Why do you keep doing this Uzima?” I asked. “It’s a call I answered. That the people who live here will at least have some medical care near them.”

$5000 helps us improve BandaGo and get it into another little clinic

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.

Thanks to your giving, Banda Health continues to focus on building technology that improves the healthcare provided by small clinics in neighborhoods and environments like Mathare slum.

We can't do it without your help!

So far 86 clinics are using our software in slums, informal settlements and remote rural villages and have recorded 852,000 patient visits to date!

Kinya Kaunjuga

Kinya brings passion, an infectious laugh and 15 years of experience in the corporate and non-profit world to Banda Health. A Texas A&M alumni with a degree in Journalism and Economics, she says, "I love doing things that matter!"