Has Muthama been notified? The go-to clinic owner when kids fall from high-rise balconies.

By Natalie Walters

A child’s terrified cry rings out at 6 a.m. in the poor, high-rise community of Builders outside Nairobi, Kenya. Residents rush to their laundry-strewn balconies to locate the source of the scream, already knowing what happened: another child has fallen from one of the balconies onto the dirt road below.

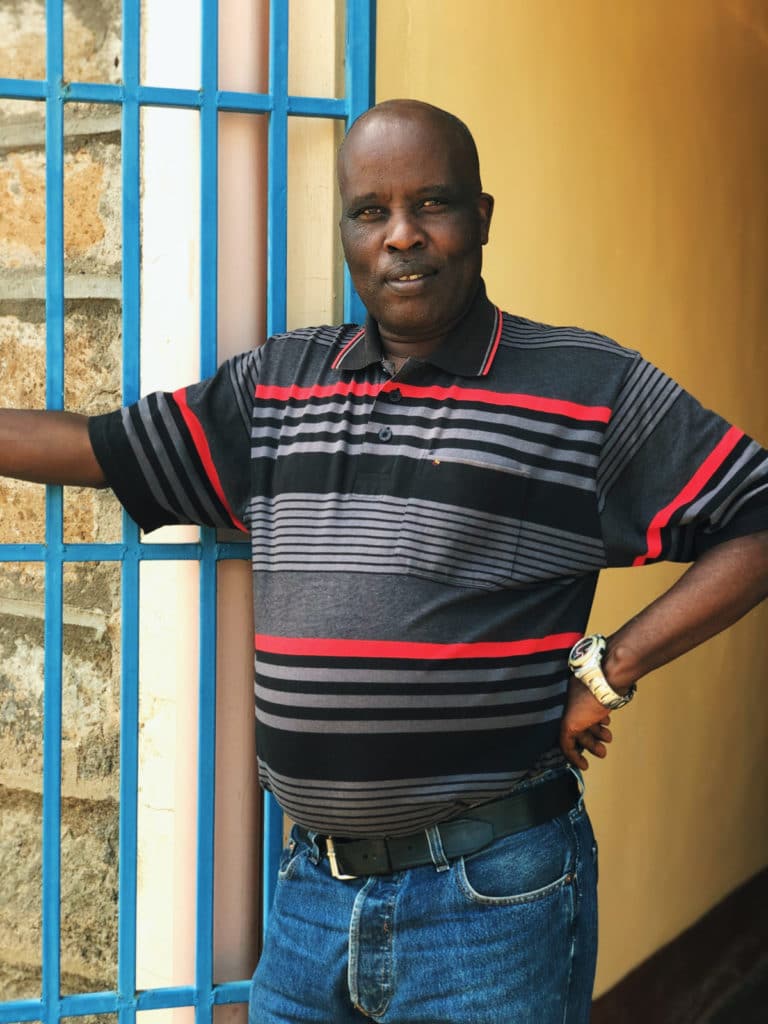

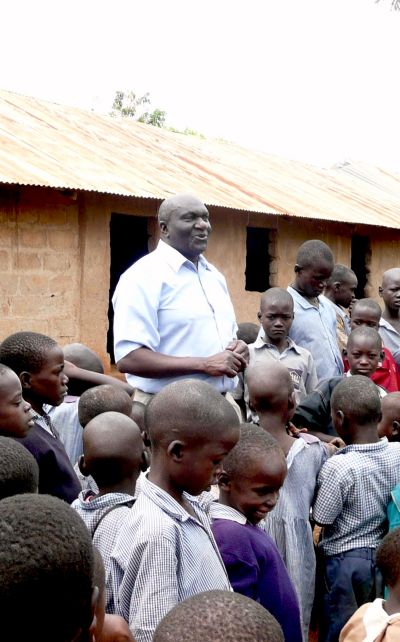

As onlookers stop to help the child, the first thing they ask is whether Stephen Muthama has been notified. He’s their go-to clinic owner for when kids trip or slip from the tall buildings.

“Has Stephen Muthama been notified?”

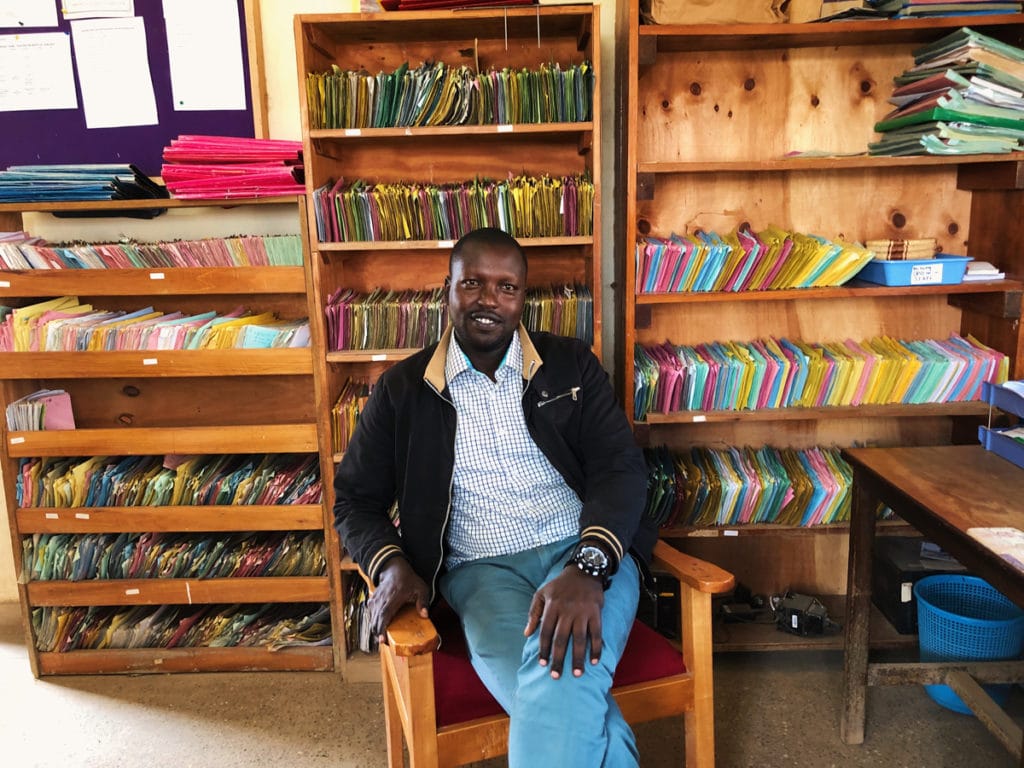

“I’ll get a call at 6 a.m. when I haven’t even showered, and I’ll have to run into the clinic because a child was running late for school so they were running and tripped and fell,” Muthama tells us in the office of his tiny three-year-old clinic in the middle of Builders.

Another scenario that happens more than you’d think possible is that someone will pour water out of their apartment onto the street, where the liquid hits an exposed electrical wire and causes an explosion. Everyone rushes once again to their balconies and leans out to get a good look at the fire and, inevitably, a child ends up leaning out too far and falls.

Muthama estimates that he cares for a child who has fallen from a balcony at least once a week. Most times, it leads to a fracture. Muthama stabilizes the child as best he can with his limited resources and then refers them to a larger hospital nearby.

After seeing their child fall from their apartment, you might think a parent would be racing to bring their child to Muthama. But actually, it’s the opposite. They often let an onlooker take their child to the clinic because they don’t have the money to pay Muthama, who they know would never turn a child away.

“Typically if someone isn’t a senior, I always make them pay,” Muthama says. “But because it’s a child, you can’t refuse service.”

“I know I won’t go out of stock with Banda.

That used to be a big problem.”

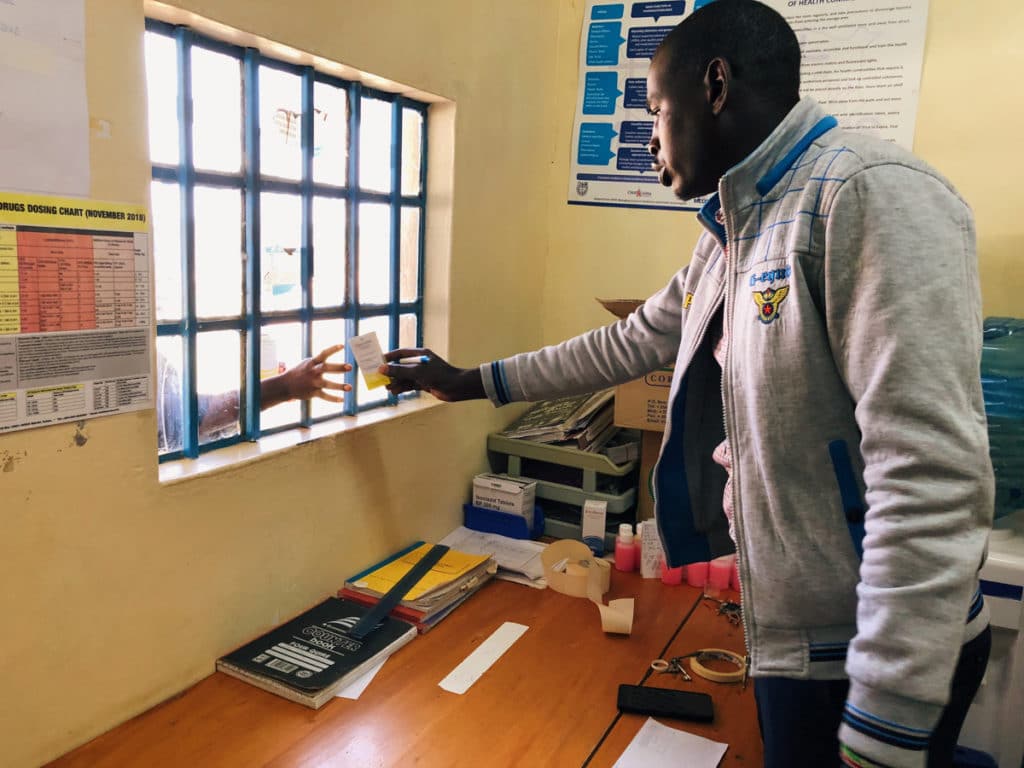

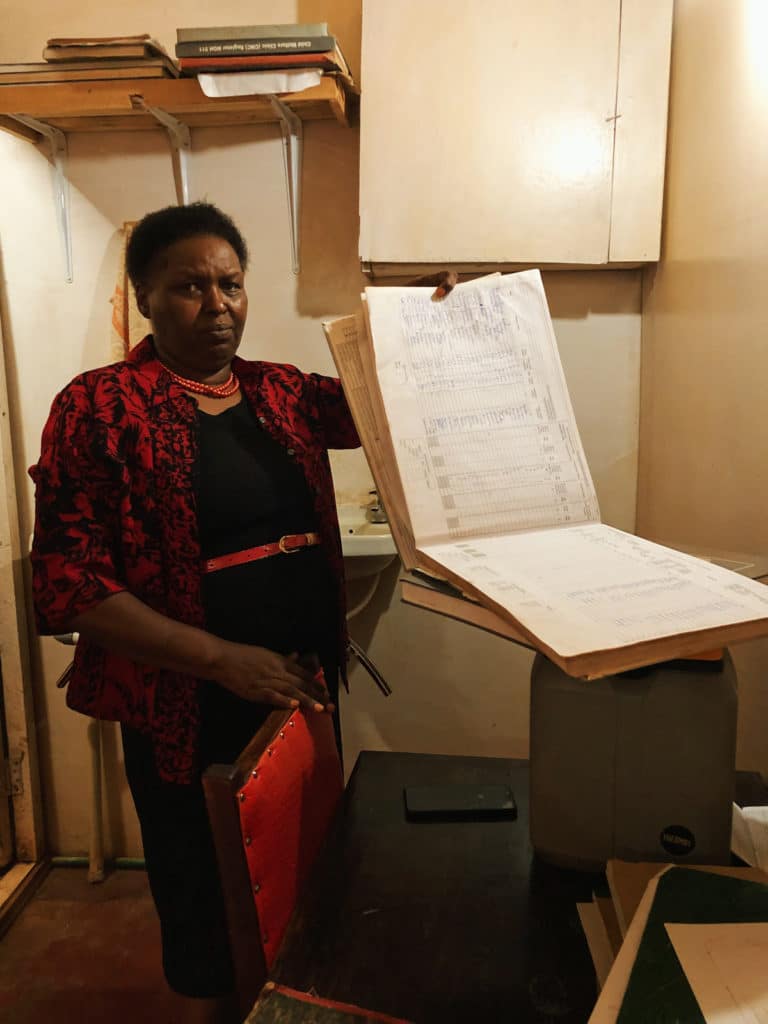

Muthama, who is working toward a degree in public health, is constantly looking for ways to improve the service he provides to his patients. One way he’s doing that is by using Banda Go’s software to help track his inventory. Whenever he has a new bottle of medicine, he enters its information into Banda so that he can keep track of when he will run out of each drug, as well as when each bottle of medicine will expire.

“Banda made my work easy,” he said. “There’s less paperwork. It’s good for stock control. I know I won’t go out of stock with Banda. That used to be a big problem.”

Muthama said that after noticing how often Banda’s software gets updated to a newer, better version, he’s been inspired to improve himself in the same way. Since he had to set up Internet service at his clinic for the first time to start using Banda, he now utilizes it in his free time to look at medical evaluation websites to stay up-to-date on treatment options.

“Whenever Banda gets an update, I always try it right away,” he said. “But now I’m learning that I need to update myself too. In between patients, there’s a lot to learn.”

Take a quick virtual tour of Stephen’s clinic, Builders Health Care Services.

You may not live in Pipeline, but you can still be part of the Banda Health community!

Banda Health exists to help healthcare providers like Stephen provide good healthcare to people who need it, but often cannot access it.

By donating to Banda Health, you help make our clinic management tool Banda Go to healthcare providers like Stephen, impacting communities like Pipeline Embakasi across Kenya and beyond with good healthcare.

Banda Go is our baby, and it’s taking a global village to raise it. Thanks for doing this with us!

Natalie Walters

A journalist from New York, Natalie is helping write stories about the clinics using Banda Go.