There are many kinds of wealth, just as there are many kinds of poverty

By Kinya Kaunjuga

Some say it’s not how you start, its how you finish. When I finally met “Mzae” (Peter Kabira), I had more than an inkling from a video I had seen that he was a remarkable human. In the video he scoffs at the $90 relocation donation from the government because it meant jostling crowds of people younger and stronger than him. Instead he had chosen to move into the highest drypoint, a toilet, and live there until the floods subsided. It was enough for me to want to meet him and find out more.

I was completely engrossed with observing every detail about him. I felt as though he was a rare specimen that encompassed an intricate combination of characteristics which had to be unearthed and carefully examined to discover how one could live past 18 into their seventies in a slum. And not just any slum, but one of the most dangerous slums in the city. Then there was the video I had seen where he spoke about surviving on a mere 10-shilling meal each day—just 7 cents in US dollars—after losing his home to Nairobi’s most devastating flood in a hundred years. His voice held the weight of someone who’d lost everything, yet was struggling to hold on.

But nothing had prepared me for his perfunctory enunciation of the Queen’s English as he delivered his words in syllables arranged in an array of skillful diction.

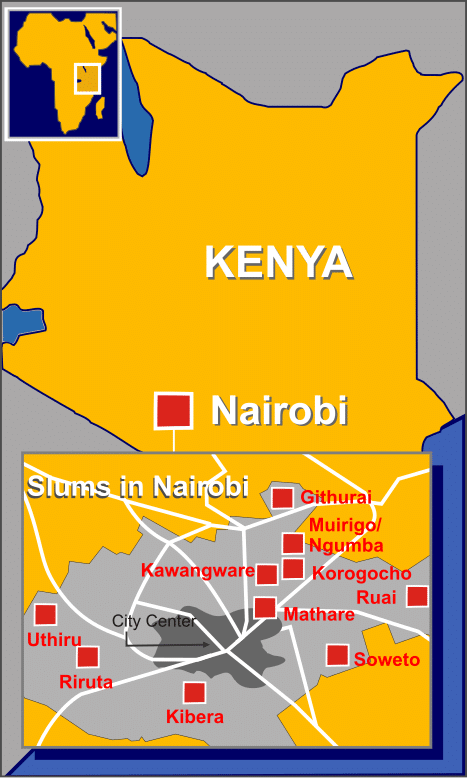

I was shocked to find out that he does not drink unlike all his other age mates in the slum, has always cooked his own meals, and was in his high-school debate club and led them to win national championships. He was born and raised in Mathare shanty (slum) in Nairobi, the capital city of Kenya, to a mother who worked for the British colonialists and they had lived with his grandmother who had done the same.

Mzae attended a nationally renowned high school which was called The Duke of Gloucester School, named after Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester by the British in 1955. It’s now called Jamhuri School after Kenya’s Independence.

He followed suit like everyone else who lived in the shanties and, right after high school, got a line job at a factory that made cooking fat, where he worked for the next 30 years of his life.

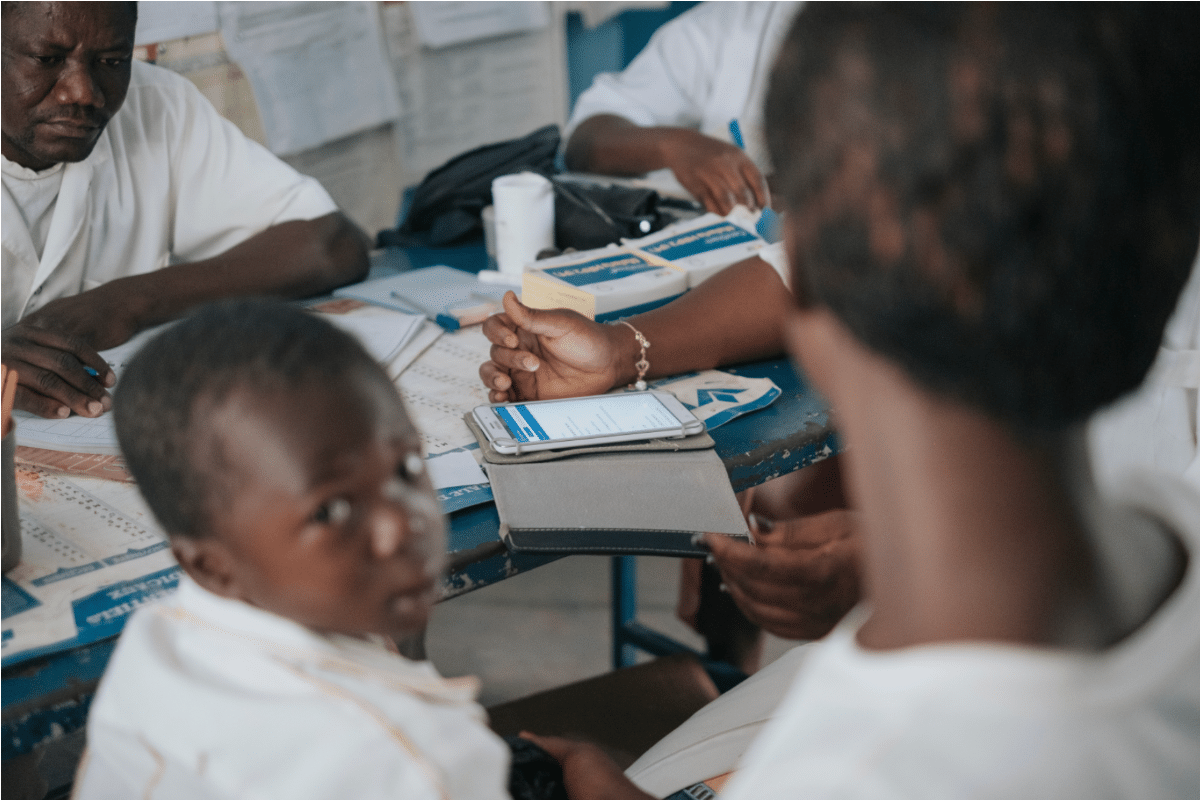

Where we work

Transforming a debate club champion

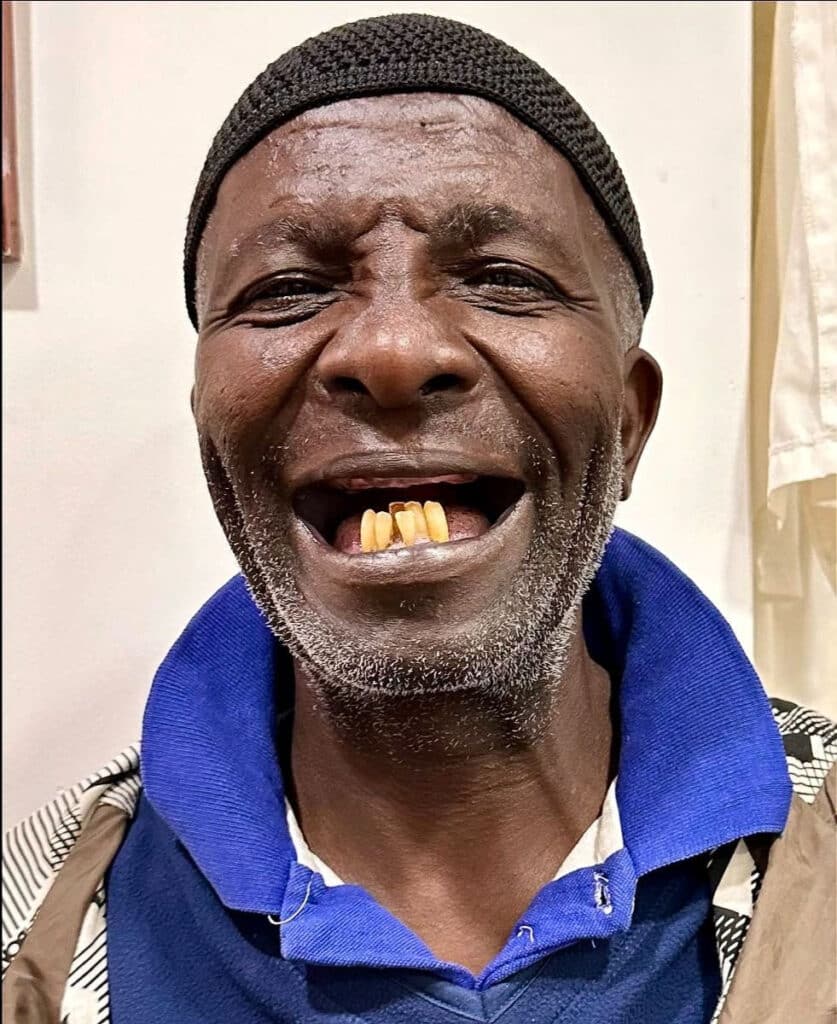

Mzae’s life with teeth:

- Children in the neighborhood: trooping after him to have conversations about how his teeth re-grew.

- Walking style: now has a pep in step.

- Long-forgotten favorite food: munching beans and soft corn almost daily.

- Sadness from losing everything at his age: overwhelming ticking time clock thrown out of the window.

- Learning complete strangers made this happen: filled with renewed hope.

- Message to donors from Mzae, “Mwenyezi Mungu Akubakiri (Almighty God bless you), you are my saving grace.”

- Financial stability: with part of donation, purchased a wheelbarrow, fills it with his favorite fruit (avocado) and sells them daily in the streets. In one month he has earned enough to pay his monthly rent and subsistence. He plans to open a small kiosk to sell the avocados and other fruit.

- Healthcare: can now afford to see a clinical officer in a small medical clinic regularly.

Thank you for your help!

Our dream of using technology innovations to bring hope to the world’s most vulnerable patients is ambitious, and we are so thankful for all of your support as donors and encouragers on this journey.

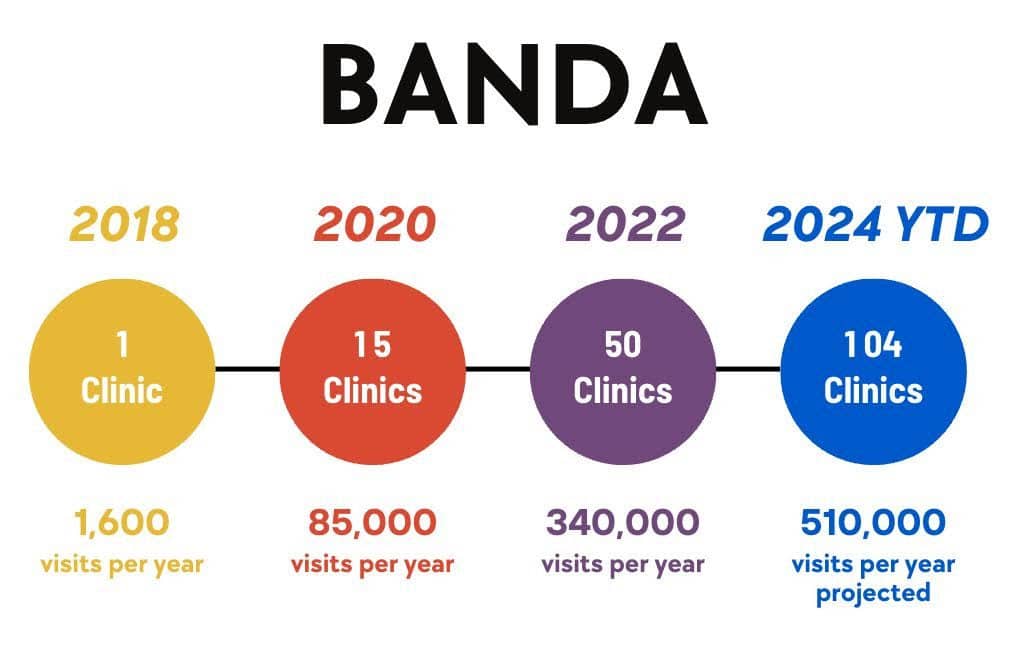

As of today 110 frontline medical clinics (small clinics that run on extremely low resources located in slums and rural villages) using our HMIS BandaGo to make their clinics more sustainable and to improve care for over 650,000 patient visits per year!

We are excited about this progress but realize it’s the one-mile marker on a 1,000-mile journey. We aim to reach 150 clinics in 2025. Thank you for making this possible with us! Steve and Wes, (Banda Health Co-founders).

Kinya Kaunjuga

Kinya, our corporate storyteller is a digital nomad. She has worked in Africa, Asia and North America. She's a Texas A&M alumni with a degree in Communications and Economics. She's met people from almost every part of the world and believes everybody has a story worth listening to.