"I was multi-tasking, asking the lady to push, and trying to stop the bleeding on the gentleman."

By Kinya Kaunjuga

He couldn’t decide which experience had been more difficult. Trying to stop the bleeding from a man’s head in the clinic while delivering a baby beside him, or holding Ondieki’s abdomen together in the street because he had been stabbed 17 times and no ambulance could get past the ambush set up by gangs.

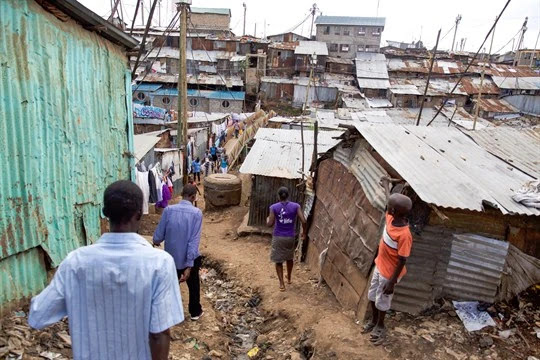

He was shocked to witness the gruesome acts on human life. After all, he was right out of nursing school. He and Uzima had been dealing with non-stop emergencies in the days following a presidential election that had brought a tribal war to the slum.

He was not afraid, he was terrified. He knew being a second-Dan black belt made him impervious, but he was also keenly aware the ghetto was a fierce place. Persistent hunger made angry and fearless contenders out of its residents.

Over the past five years, 26-year-old Balala has gained the respect of the community where he was born and raised. In a Taekwondo class of 70 students which he joined when he was seven, he is one of the eleven students still living. The rest have died from gang-related violence.

The second day we sat down to talk, he was pensive but accommodating, which seemed to be his nature. To get him relaxed for our interview, I gently prodded him about his day. Like a tired hero arriving home from battle, his drooping shoulders began to straighten as he spoke and his weary eyes slowly regained their glow.

“Say for you, Kinya, your place of work is known. And your line of work is known. Same for the people in the ghetto, we know their line of work. We know who is involved in theft and other activities. And the wages of sin is death. So we know that at the end of the day, death is coming. Just a few minutes ago, I was at the Mama Lucy Hospital morgue, where I went to identify a 16-year old friend. He underwent mob justice in the night. And that is the trend in this ghetto.”

As if that morning’s task had transported him four years back in time, he continued, “During the 2017 general elections, myself and Uzima worked tirelessly. Mathare is divided in a way that when war erupts, zones are divided by tribe, like a Luo zone and a Kikuyu zone. I was the only person who could walk from this place to a Kikuyu zone, bring a sick person to our clinic and then call an ambulance. In fact, those Kikuyu boys, most of them had my phone number. I don’t know where they got it, but they would call me Daktari, or call me by name, and ask me to go rescue people who were injured. I would go there terrified, but because I had already resolved to serve, I would just go.”

A prophet is without honor in his hometown, and it took time for the community to trust Balala as a nurse rather than as the boy who did Taekwondo. They found it hard to believe that someone who grew up in circumstances similar to theirs could work in a clinic and help treat them. However, there was one person who never doubted the slum child could help his community – “Uzima” White Indimuli, the owner and founder of Uzima White Clinic.

When Balala asked White to teach him first aid, Uzima asked him to learn nursing instead. The two struck a deal, and Balala agreed on condition that Uzima would find him a job as far away from the slum as possible. Uzima took care of everything Balala required for college, including travel to a nursing school under the tutelage of a consultant surgeon, Dr. Mleche.

By the time Balala completed nursing school, Uzima’s clinic – running in the makeshift structure – had become tantamount to a lighthouse for many suffering in the dark sea of poverty. Balala could not turn his back on his community.

“It was hard at first before the people got used to me being their nurse, but thank God, I and the community managed to adjust.”

sound bites

Nurses are drawn to those in need of rescue. When Balala found Tyson, he was a young boy being beaten by a crowd for stealing. He begged them to let him take the injured boy to a hospital. Years later, Ty (as Balala fondly calls him) found his rescuer on Facebook and thanked him for stopping the angry mob from cutting his hand off that day. He had returned to the countryside where he now lives peacefully.

“All that we’ve done with Uzima for the community has been a calling.”

“I come to the clinic even outside my shifts when there are calamities. For instance flooding of the houses built near the river, or fires that catch the mabati (tin) houses.”

“I’m part of the community with my everything, beyond treating people, being a child of this slum.”

“Every so often Ondieki comes to the clinic to greet me. When he was stabbed just a few meters from here, I was called to go help.”

“It weighed heavily on me that the ambulance could not come, so we tried to treat his wounds while people scrambled to find a car. When the hospital where Ondieki was later treated asked if we had an operating room to care for patients, I told them no, all we do is save lives with what we have.”

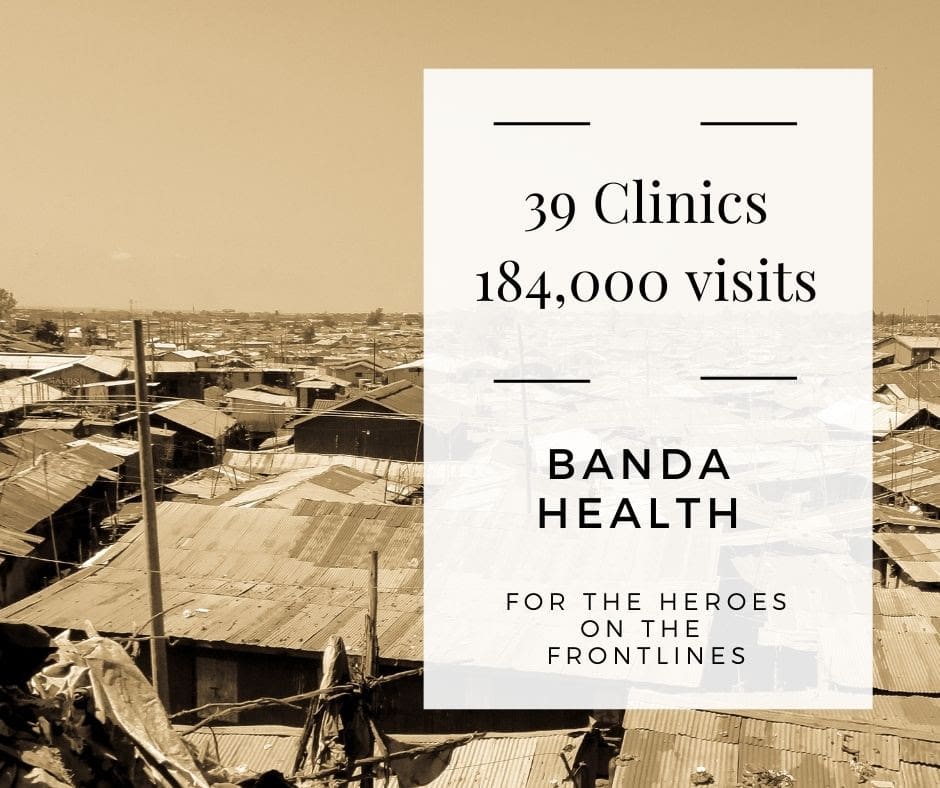

You can empower frontline teams with technology

“Uzima” White Indimuli runs what we call a frontline clinic because it is the first or second place a patient in a slum, informal settlement or remote village goes to for medical care. His clinic is open 24 hours a day with 15 beds and 22 staff and he uses Banda’s clinic management software.

They began using BandaGo this year. “We usually treat over 200 people per week. Before we got BandaGo, we didn’t even know how much money we were getting, how many drugs we were using and for what, or how much we had spent. But now BandaGo keeps records for us. It has really helped us to realize how much we make and spend. Now we are happy!”

Read more about White “Uzima” Indimuli in this story: We dance.

Kinya Kaunjuga

Kinya brings passion, an infectious laugh and her 15 years of experience in the corporate and non-profit world to Banda Health’s operations.

A Texas A&M alumni with a degree in Journalism and Economics, she says, "I love doing things that matter!"